Ayushman Bharat for its Disabled

By Arunima Rajan

Why India's dispossessed disabled population needs to be included in its universal healthcare scheme

Early this month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi introduced the Ayushman Bharat Vaya Vandana card, specifically targeting senior citizens aged 70 and above. This extension of the existing Ayushman Bharat-PM-JAY (Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana) scheme is expected to provide an additional financial cushion of up to Rs 5 lakh, annually, ensuring that economically weaker seniors receive the necessary healthcare services without the added burden of medical costs. However, this scheme is available to all senior citizens above the Age 70, regardless of their financial status.

The Ayushman Bharat scheme, also known as Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY), is a health insurance scheme in India which provides free or low-cost health coverage for low-income families. At present, about 60 per cent of India's nearly 1.3 billion people live on less than around Rs 300 a day.

On the heels of this move, the question of whether persons with disabilities, irrespective of their financial status, should be similarly included in the ambit of the Ayushman Bharat scheme is quickly gaining ground. Given that most persons with disability are possibly part of India's burgeoning poor. To this end, a coalition of organisations working in the space of disability rights had petitioned the Government. The ask is to broaden the access, even if it means prioritising it, to India's national healthcare scheme to underserved populations, such as those with disabilities, irrespective of their financial status.

This petition is supported by findings from the National Disability Network. According to its data, based on a survey comprising more than 5000 respondents, taken to assess if, and how many, disabled persons in India have health insurance coverage, it reveals that over 80 per cent of the participants did not have health insurance. In this group: 54 per cent of them had previously applied for insurance but had been denied.

In light of these findings, disability advocates argue that the issue of health coverage for disabled persons goes beyond policy adjustments alone and requires a fundamental shift in the way socio-economic systems and policies operate. These include Government-instituted grants, privately funded programmes, and wage schemes, which, they believe, should prioritise, protect and support this vulnerable group. According to the 2011 Census of India, 2.21 per cent of the total population, or 26.8 million people, were disabled. And this number is only growing.

The below table offers a broad overview of the population spread.

Snapshot of Disability Statistics

More recently, according to the 2019-21 National Family Health Survey, 4.52 per cent of India's population, or 63.28 million people, have disabilities.Globally, the World Bank estimates over a billion people live with disabilities, with 80 per cent residing in developing countries, including India.

For disability-related healthcare (which includes, and is it related to the disability itself or other health issues too, which may not be stemming from the disability per say), a person incurs an average out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) of Rs 2,477 per person, per month.

For perspective: on average, 20.32 per cent, almost one-fourth, of a household's monthly consumption goes toward OOPE to manage life with disabilities for one of its members. Such a significant portion of household consumption being diverted to healthcare has the potential to push families into debilitating poverty.

Disability, according to the 2023 study titled: Measuring the Financial Impact of Disabilities in India: An Analysis of National Sample Survey Data, disproportionately burdens poorer households, eating into 30.4 per cent of income for the poorest versus 17.0 per cent for the richest. Catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) due to disability affects 57.1 per cent of households underscoring significant financial strain on vulnerable populations. Catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) arises when a household is compelled to cut back on essential expenses, such as food and shelter, and liquidate assets, or take on debt to meet the medical costs for a family member with a disability.

Gurgaon-based public health expert, Anubha Mahajan, founded Chronic Pain India in 2017 to raise awareness about chronic pain conditions. A medical professional herself, Mahajan is living with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Her battle with this invisible disability drives her to support others facing similar struggles. Giving voice to people with disabilities, Mahajan believes that including individuals with disabilities in the Ayushman Bharat scheme will create a much-needed safety net, addressing the significant barriers this group faces in accessing healthcare.

However, she maintains that the primary challenge is not securing insurance per say but addressing the glaring gaps within policies related to healthcare access for disabled persons.

"The main healthcare challenge isn't just for people with disabilities. The real issue lies in the numerous exclusions in our health insurance policies," Mahajan explains. "Anyone with a long-term illness can find necessary treatments out of reach because they're not covered." She highlights that many treatments, including routine and necessary procedures, are left uncovered, compounding the financial strain on those already managing disability-related expenses. "For instance, cataract surgery can be one needed by anyone, irrespective of someone being disabled or not," she explains.

A person without a disability might be in a better position, financially, to deal with this. Or they may have avenues or opportunities they can avail of owing to their otherwise healthy disposition. But someone with a disability faces additional expenses, apart from their existing ones, to do with their disability. Imagine needing a cataract procedure, which isn't covered under insurance: “Where would you find the Rs 50,000 needed for it?,” she implores. Mahajan points out that people with disabilities also often require accessible equipment, such as adjustable chairs or accessible beds, which aren't commonly available in government hospitals.

Accessibility Challenges in Public and Private Facilities

Mahajan notes that many of these services are primarily offered in private facilities, and there is limited access to these in public hospitals. This creates a substantial financial burden as costs for specialised care accumulate.

A person with autism, for instance, she explains, needs a quiet space for their treatment. This may necessitate a private room. This has nothing to do with comfort but, here, the opting for a private room may raise questions about insurance coverage.

Mahajan has her own experience to share, navigating these financial and accessibility challenges.

And while she may not belong to the low-income group, per say, one can glean from her experience and get a glimpse into how challenging it is for a person with disabilities to navigate such uncertainties in life. Furthermore, imagine if it's so hard for a person with means: how much harder it is for those with scant means!

"During a personal emergency in Bangalore, I needed immediate admission. The hospital required an advance of Rs 15,000 per day. I was concerned about whether I had enough on my card to cover this," she shares. The cost was significant, and arranging funds during an emergency was incredibly stressful, she adds.

This, in addition to her afflictions.

The Reality for People with Disabilities During COVID-19

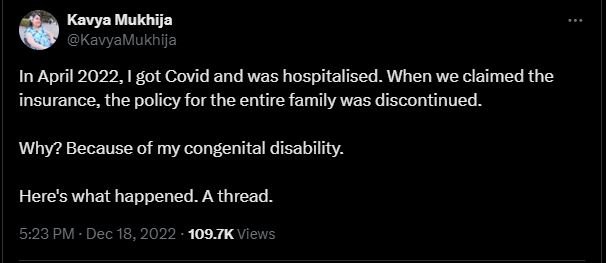

Mahajan also shares a story of one of her team members, who doesn't come from means, and uses an electric wheelchair. During COVID-19, this individual contracted the virus and required intensive care. The Government had mandated COVID-related coverages in all health insurance plans. Yet, her insurance company denied the claim due to her pre-existing condition and cancelled her policy without a premium refund.

During their legal struggle, the Insurance Ombudsman ruled in her favour, but the insurance company resisted compliance even after the ombudsman's direction, she alleges on her social media handle.

According to Mahajan, this situation caused significant distress for her and her family, especially since she needed daily care and had substantial expenses stemming from her reliance on an electric wheelchair to start with.

Even today, accessibility remains limited, particularly for electric wheelchair users. They are forced to plan for high costs incurred and opt for pricier options for ease of access.

For instance, accessible restrooms in five-star hotels, where accessibility is prioritised, have to be chosen over budget, not for the want of comfort but the lack of an alternative. They really don't have any other option or way around but to. Imagine being forced to pay more because your condition prevents you from opting for the basic versions; because the basic version isn't built in a way to be accessible to you. Arman Ali, a disability rights activist, with over two decades of experience emphasises the lack of awareness about the insurance needs of persons with disabilities.

Ali is also the Executive Director of the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP).

"Both families and insurance companies often fail to understand a disabled person's requirements," Ali explains. While the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) has issued guidelines for coverage, the policies available are limited. "Most products offer only a mere ₹5 lakh in hospitalisation cover, but they have high premiums,” he says.

Apart from this, even if there is a policy, awareness about it remains low, but more importantly affordability becomes a huge issue, adds Ali.

"I know people with muscular dystrophy who are 50-years-old and still denied insurance.” Insurance companies often view disability as a terminal condition, which is not fully accurate.

The insurance company considers disability as something that can lead to a person’s death, which isn't so. For instance, a disabled person who didn’t require hospitalisation/surgery until they do, or even when they contract COVID, which may have led to hospitalisation, they are still denied insurance coverage, despite no history of hospitalisation prior to this.

“It took me eight years to secure health insurance. When I finally got it, they listed several pre-existing conditions that I didn't have. After I did tests and submitted reports, they removed those exclusions,” adds Ali.

The Cost of Disability and Financial Burdens

Ali and Mahajan highlight that living with a disability often involves added costs. Ali explains, "For a person with a disability, living an equivalent lifestyle (as compared with someone with no disabilities) means higher costs. They cannot rely on public transport or the metro and often use expensive cabs. Many of us are unable to participate fully in the labour market."

He also points out: while people with disabilities might need health insurance, more than others, they are often the ones denied coverage.

Ali mentions the Niramaya scheme, which provides ₹1 lakh in coverage for people with autism, cerebral palsy, and developmental disabilities, but notes that it is limited in scope, in terms of the range of conditions covered. The categories covered are all but four.

“Numbers drive insurance companies. They might be more willing to offer broader coverage if they see enough demand (for such instruments),” he adds.

Why Inclusion in Ayushman Bharat Is Critical

Ali stresses on the connection between disability and poverty, emphasising on the importance of affordability. "This is why we're asking the Government to include people with disabilities in the Ayushman Bharat scheme,” he says.

“There should be a genuine effort to ensure that people can choose between Ayushman Bharat coverage or a private insurance plan," he adds. "Ironically, even those who can afford insurance often face rejection. Just last week, someone with a spinal-cord injury was denied coverage (under a private scheme).”

A Call for Government Support and Accountability

Ali and Mahajan call for increased awareness and accountability within the insurance sector. Ali believes government subsidies or incentives for insurers could help make policies more accessible for people with disabilities. "Investment in the disability sector is essential," he adds. For people with disabilities, the cost of simply living an equivalent lifestyle, at par with even a low-income person without disabilities, is often higher, and health insurance is a crucial support that should be accessible and affordable, says Ali.

Both advocates see Ayushman Bharat as a vital opportunity to extend meaningful support to individuals with disabilities in India. "The goal should be true accessibility," Mahajan adds.

According to both advocates, Ayushman Bharat could be a significant milestone in ensuring that everyone, regardless of their disability, can access and afford quality healthcare.

Healthcare as a Fundamental Right

The General Secretary of the National Platform for the Rights of the Disabled (NPRD), V. Muralidharan, who is also a prominent disability rights activist in India, however, has a different take on the issue.

With a background in disability advocacy spanning decades, Muralidharan argues that the nation's approach to disability needs a transformative shift—from viewing disability through a charitable or altruistic lens to treating it as a fundamental rights issue.

"Health is a Right, not a benefit," he says.

"It is a basic right and the Government should provide free health services to everyone, including people with disabilities."

He stresses that focusing on insurance alone misses the bigger picture, advocating instead for more significant public investment in health infrastructure.

"Disability is incredibly diverse, and the 21 categories defined by law are just a starting point. Each type comes with its unique challenges. For instance, a wheelchair user has completely different needs from someone with a speech impairment,” he adds.

Snapshot of laws pertaining to disabled persons

Snapshot of laws pertaining to disabled persons

He explains that even basic accessibility remains elusive. "The ramps we see in many places aren't functional for wheelchair users, and facilities like hospital beds and scanning centres are rarely designed with different kinds of disabilities in mind.”

The Numbers That Are Missing

Muralidharan says India's disability statistics remain outdated, and there's a gap in accurate data.

The 2016 Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act expanded the definition to 21 categories, bringing an estimated 10-15 per cent of India's population under its scope. However, close to 8 years later, without more recently collected data, effective policy-making remains difficult.

A Medical Gap in Understanding

"Doctors often don't understand disability," Muralidharan points out, highlighting the need for better training in medical schools too. "Disability is largely absent from the curriculum, so healthcare professionals are often ill-prepared to treat patients with disabilities effectively."

Doctors also carry with them the same stigma, prejudices and attitudes towards disability, like the general public. Some presume that all the health issues a person has is on account of his disability, he adds.

A Tax on the Marginalised

He brings attention to a critical issue: the GST on assistive devices. "In India, pooja samagri (items for religious rituals) is exempt from GST, yet assistive devices like wheelchairs are taxed," he adds ironically.

For people with mobility challenges, a wheelchair is akin to a part of their body, he argues, serving as an extension of themselves. "Assistive devices are essential, not luxury items, and taxing them is unjust!,” he adds.

Muralidharan quotes instances that draw a contrast with other countries. "In the UK, for example, health conditions, such as cancer and diabetes, are considered disabilities, and in the US, even gluten intolerance is recognised as a medical issue. In India, we're still far from understanding or accommodating the true scope of disabilities."

Limited Funding and a Leadership Void

India, he points out, has declared itself a five-trillion-dollar economy yet taxes people with disabilities: a small, already marginalised community, on essential tools for survival.

The National Trust, a government body for the welfare of people with developmental disabilities, has operated without a chairperson since 2014. "An autonomous body, established by an Act of Parliament, is left leaderless. What does this say about the importance given to disabled people in this country?,” he rues.

"Most people with disabilities come from poor backgrounds, and their disability often exacerbates their poverty," Muralidharan adds.

Disabled persons are the most vulnerable of the vulnerable. The poorest of the poor. The primary purpose of insurance is to provide protection against future risk, accidents and uncertainty. Offering them the safety net of Ayushman Bharat will prove to be a small but veritable step: a start to improving their lives by offering them the safety net they need to navigate their already challenging lives.